Did you know that as climate change intensifies rainfall patterns, increased water erosion on trails and natural areas can undermine soil stability, degrade infrastructure, and threaten visitor safety?

Climate change affects precipitation form and timing. Warmer winters often result in less snowfall and earlier melt, shifting more precipitation into rainfall. This extends wet seasons and places excess strain on trail infrastructure originally built for winter snows and spring showers, who now have to face significantly more rain than designed for.1 Because of this, trail components like drainage routes and bridges must now handle water volumes well beyond their original design, causing flooding and erosion.

Recent findings from the U.S. Geological Survey highlight how heavier, more frequent extreme rainfall events increase runoff and soil loss.2 In areas with steep trail slopes, sheet and rill erosion, a type of water erosion that strips the uppermost layer of soil, can dramatically widen paths and form gullies to compensate for the extra rainfall. These erosion patterns jeopardize both trail integrity and surrounding ecosystem health as the runoff brings soil into aquatic environments.2-3

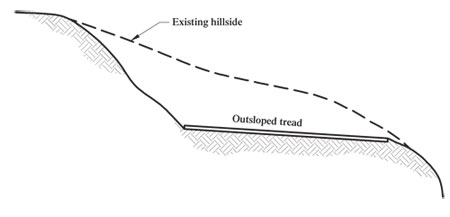

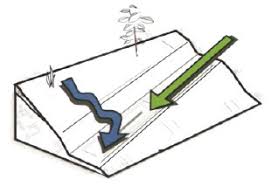

Trail grade and slope matter are some of the key factors in combating erosion. Trail grade is like the steepness of a trail: when going up or down a hill, you are experiencing changes in the trail’s grade. The slope of the trail, specifically the outslope, is like the tilt of the trail. It is the slope of the trail between the side of the hill it runs against and the bottom of the hill.4 To have durable trails, builders must take the combination of the two slopes to ensure water does not gather or pool on the trail, preventing soil runoff.

Trails built along the fall line, the path water flows downhill, are especially at risk as runoff gains speed and volume. Sustainable trail design must take this into account, avoiding running parallel to any fall line. Things like tight switchback turns, grade reversals, and special drainage routes called waterbars can help deflect water and reduce erosion.2-5 Without these design features, trails are prone to washouts and become hazards to both hikers and wildlife as water builds momentum and strips away earth.

Vegetation loss compounds these issues. With rising temperatures, drought, and extreme storms weakening plant communities, environments with otherwise stable soils and root systems are suffering from downpours and droughts at the same time.3-6 Without stable ground cover, soil becomes loose and susceptible to being carried away by runoff. In turn, the loss of soil means that plant life suffers from having less space to grow.

The result of these climate extremes is that trails and park areas face more frequent damage, closures, and expensive repairs. These closures threaten the security of parks as a staple in american life, making nature scarcer and scarcer in the modern day. In addition, hikers face increased hazards, such as flash floods and unstable trails, even at iconic destinations like Yellowstone and Denali.7

What can you do to help?

To start, when you are enjoying local parks, try to stay on designated paths; the parks were designed that way for a reason, and creating new paths could make new channels for water to run along. You can also advocate for parks to be resilient towards climate change or support climate-first policies with your local government or park agencies. Beyond this, you can spread the word about the threat of climate change to everyday people and local areas.

- Wilson, Tamara, et al. “U.S. Geological Survey Climate Science Plan—Future Research Directions.” Circular, vol. 1526, Mar. 28 2025, pubs.usgs.gov/publication/cir1526/full, https://doi.org/10.3133/cir1526. Accessed 19 June 2025.

- Marion, Jeff , et al. “Sustainably Designed Trails: Recent Recreation Ecology Findings on Design Factors Affecting Soil Loss.” U.S. Geological Survey, 17 Sept. 2018, http://www.usgs.gov/index.php/centers/eesc/science/sustainably-designed-trails-recent-recreation-ecology-findings-design-factors?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Accessed 19 July 2025.

- Aldin, Shojaeezadeh S., et al. “Soil Erosion in the United States. Present and Future (2020-2050).” ArXiv, Cornell University, 14 July 2022, arxiv.org/abs/2207.06579?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Accessed 19 July 2025.

- Doyle, Ruth , et al. “Accessibility Guidebook for Outdoor Recreation and Trails.” United States Department of Agriculture, Apr. 2006, http://www.fs.usda.gov/t-d/pubs/htmlpubs/htm06232801/page24.htm. Accessed 19 July 2025.

- Thieler, Robert, et al. “USGS Fact Sheet 095-02: Vulnerability of U.S. National Parks to Sea-Level Rise and Coastal Change.” U.S. Geological Survey, 29 Sept. 2016, pubs.usgs.gov/fs/fs095-02/fs095-02.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Accessed 19 July 2025.

- “WEPP Model Documentation : USDA ARS.” U.S. Department of Agriculture, 11 July 1995, http://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/50201000/WEPP/usersum2024.pdf. Accessed 19 July 2025.

- McGrath, Jenny. “Photos Show the Impact of Climate Change on National Parks.” Business Insider, 3 Dec. 2024, http://www.businessinsider.com/photos-climate-change-national-parks?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Accessed 19 July 2025.

Leave a comment